Blood Brothers, by Elias Chacour

Blood Brothers, by Elias Chacour

My dear friend and Lutheran pastor, who visited Palestine in 2014, advised me that

Blood Brothers was a good introduction to the history of the conflict in the Middle East.

Until a few years ago, I only knew one side of the Palestine-Israel story. Several people from

my church started a Holy Land team and regularly visit Palestine. We've had many speakers on the topic, including Lutheran bishop

Mitri Raheb (who just won the 2015 Olof Palme peace prize),

Rabbi Ned Rosch (representing Jewish Voice of Peace), and other speakers. So I was reasonably well informed before starting this book, but

Blood Brothers gave me a more personal, home-grown perspective.

A few months ago, we discussed Blood Brothers at our church book group, and we had two special guests: a friend who is Syrian, Hazar, and her dear friend, who is the great-niece of Fr. Elias Chacour, author of this book. A deeply emotional, heartfelt conversation ensued as they both shared stories of loss and sadness about their homelands.

One of Elias Chacour's mentors, Fr. Longere, gave this advice during a final lecture:

"If there is a problem somewhere, this is what happens. Three people will try to do something to settle the issue. Ten will give a lecture analyzing what the three are doing. One hundred will commend or condemn the ten for their lecture. One thousand people will argue about the problem. And one person--only one--will involve himself so deeply in the true solution that he is too busy to listen to any of it. Now...which person are you?"

This is the central message of the book...Fr. Chacour dedicated his life to building peace among nations and religions, even though his life and his family's was upended by the Israeli occupation of Palestine.

The most important message about this book is that there's so much more going on in Israel and Palestine than what meets the eye (or crosses our path via western media).

Blood Brothers begins when Fr. Elias Chacour is just a small boy, when his family had close relationships with Jews in his community. Peaceful farmers, his family did not have a lot of money, but they were rich in love and their Christian faith.

I learned in the book that the desire to form a Jewish homeland in Israel did not begin after the Holocaust. In fact, the idea first sparked in 1897 in Switzerland, at a conference "to lay the foundation stone of the house which was to shelter the Jewish nation." Over the years, many western countries talked about creating a homeland for the Jews.

In 1917 Jewish Zionists aligned themselves with Britain's Christian Restorationists, a group that believed they might bring to pass the second coming of Christ by creating a state of Israel. The intentions were not necessarily pure either. British Lord Balfour supported the creation of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine, while at the same time playing a major role in passing the Aliens Act in 1906, which expressly sought to exclude Jews from Great Britain. He also did not care at all what the Palestinians thought about this.

Through the 1920s, European immigration to Palestine increased and Zionist leaders became less guarded about their plan to institute a Jewish state. Many Zionists were ill at ease with those who insisted on Jewish "predominance" in Palestine. Yitzhak Epstein, an agriculturist, warned the Zionist Party that they "had wrongly consulted every political power that held sway over Palestine without consulting the Palestinians themselves..." and he worried about Palestinian resentment. He argued that the immigrating Jews should help Palestinians find their own identity and open to them the new Jewish hospitals, schools, and reading rooms...however, he was staunchly opposed.

By the 1930s, immigration from Europe was rising like a flood, with no intervention or plans by the British. In 1936, Palestinian leaders called for a general strike, as they were losing power over their own homeland...the strike lasted for 6 months, crippling commerce. But violence increased and in 1938, the protests were finally crushed.

Pres. Roosevelt held off the Zionists and wanted to open the free world to the victims of the Holocaust, but Pres. Truman had a different plan. The Zionist lobbyists argued that admission to Palestine was the "only hope of survival" for the Jewish people. The exhausted British found themselves pressured by the White House, even as they watched their mandate government in Palestine blitzed by a campaign of terror. In 1947 they announced their plan to surrender their mandate. And violence spread unchecked.

Then came the Holocaust, when many western nations refused to take in Jewish refugees. Chacour does not blame the terrified masses of Jewish immigrants who fled to Palestine. He says they were pawns of the Zionist leaders. Upon their arrival in Palestine they were indoctrinated against their so-called new enemy: the Palestinians.

In 1950, 50,000 Jewish people were celebrating Passover in Baghdad, Iraq. (More than 130,000 Jews lived in Iraq at the time, the oldest Jewish community in the world.) A small bomb was hurled from a car speeding along the river, and shock waves rocked the community. Leaflets appeared the next day, urging Jews to flee to Israel, and 10,000 signed up for emigration immediately. Then a second bomb exploded, then a third, killing several people outside a synagogue. By early 1951 Jews fled Iraq in panic until only 5,000 remained in the country. In the end, 15 people were arrested in connection with the bombing, and they were Zionists. They had thrown bombs at their own people to touch off a panic emigration to Israel. Israeli Prime Minister David Ben Gurion and others knew of the plot in advance.

But back to Elias Chacour's story. During the Zionist takeover of Palestine, Israel destroyed 450 Palestinian villages, including Chacour's. He and his family had to flee their orchards and house to settle in a nearby village that was much more shabby than their own. Chacour was eventually sent to seminary and became a priest and then a bishop.

Even though his family's lives were torn apart by the Israeli Zionists, he does not hate them. Instead, he shows compassion to them, the true biblical "turning the other cheek," because he keeps in mind what happened in the Holocaust. He has dedicated his life to bringing Jews, Christians, and Muslims together...through activism, advocacy, and community building. At a young age, he and other Palestinians were unfairly branded as "terrorists" even though they were not. Given the Palestinian apartheid and unfair treatment they have received, it's understandable why they would want to protest. But Chacour has chosen a nonviolent path in spite of what he has seen and faced.

He tells a touching story about arriving in the deeply fractured city of Ibillin, where he arranged to have three nuns visit and reach out to the villagers. He hoped the sisters would be able to do what he had not yet been able to do: broker peace. Even after the tension began thawing, enemies still existed. One day Fr. Chacour locked the church doors and exhorted them to act like Christians and forgive each other.

His mother's final message to him before she died was, "Be strong, Elias. What you do matters. Especially for the young ones."

The book ends with Fr. Chacour asking questions of Palestinians, Israelis, and westerners. "How can you take on yourself the right to decide who is the terrorist? Who is the fighter for liberty? How do you find it your right to judge?"

Coauthor David Hazard shares an anecdote in the afterword about a visit to a Gazan refugee camp, where he spoke to a 17-year-old Palestinian girl. She told how she witnessed her teenage cousin being shot through the head after he picked up a rock in response to Israel soldier taunts. She accused him and all Americans of knowing about these daily abuses against Palestinians but not caring, and even supporting the conservative Israeli forces that sponsor these acts. When Hazard tried to explain that Americans don't know about these things, she said, "Of course Americans know we're suffering over here. You're the most powerful nation on earth. And everyone has a television. I know you know."

In the group at my church, our guests--Hazar from Syria and Fr. Chacour's niece, who is Lebanese, emotionally spoke of their homelands and the misperceptions people have about the real story in the Middle East. The following month, we discussed

Blood Brothers at my regular book group, and my British friend Niki spoke about what she learned about Palestine and Israel growing up, a much more complex and multilayered picture than what we were fed in the U.S.

We are so uninformed and ignorant. So much of the conflict and strife in the Middle East, hatred between Muslims and Jews, comes down to this conflict in Palestine. And until it is resolved, nothing will get better.

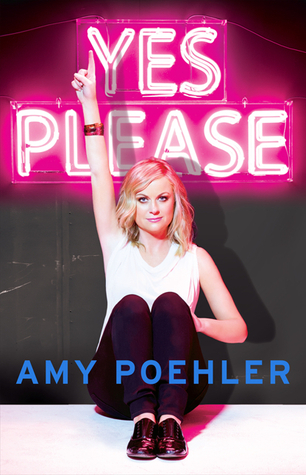

Yes Please, by Amy Poehler

Yes Please, by Amy Poehler